Return to Listing

February 10, 2022 / Jackson

Jello Baby Science at Jackson

Jello Baby: Understanding Thermal Energy

On February 7, Jackson Middle School students in Mrs. LaBorn’s 6th-grade science classes participated in a fun outdoor experiment while learning more about thermal energy.

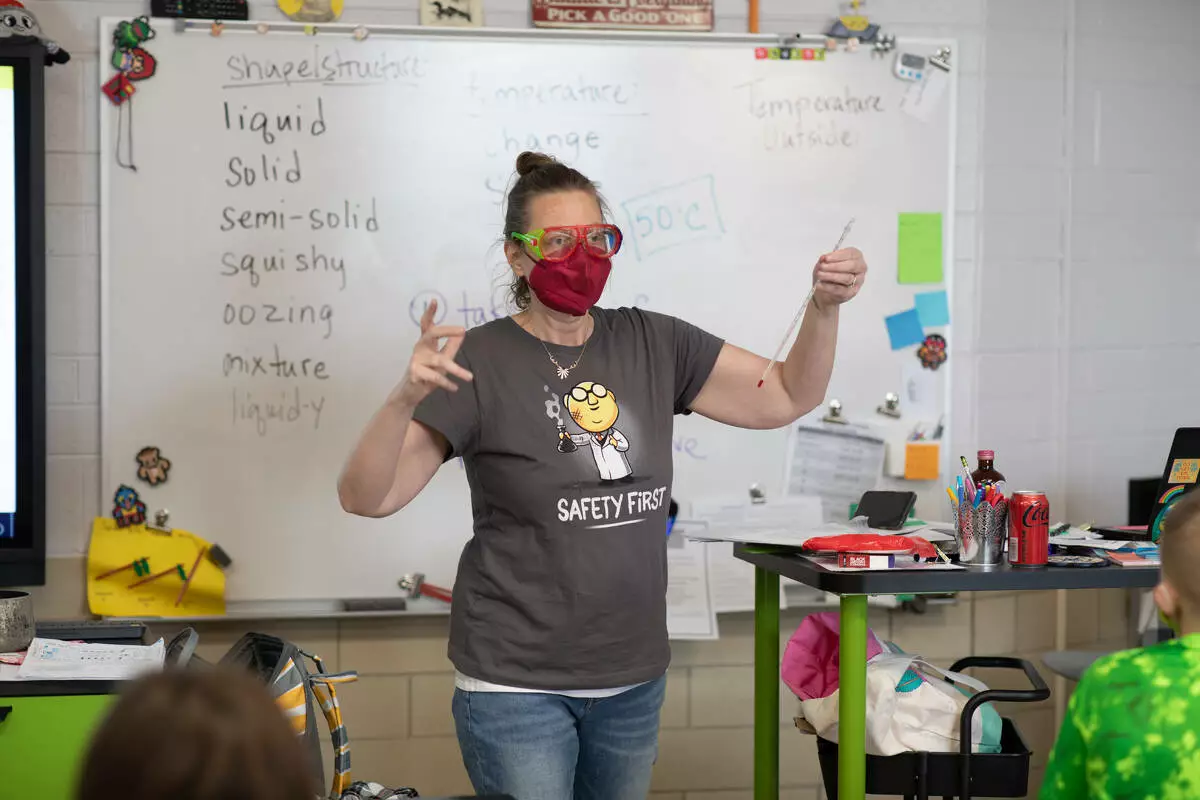

“Their objective was to apply their understanding of thermal energy to design, construct, and test a device to conserve or limit thermal energy loss,” said Mrs. LaBorn, a science teacher at Jackson Middle School.

“Jello Baby” was the term the class used to describe a red liquid cup of jello. “They were really excited about this lesson. They needed to build a device to keep their “jello baby” from freezing to death,” said LaBorn.

The experiment allowed students to creatively design a solution to solve a problem while applying the science they had been learning. Specifically, hotter molecules are moving faster, and will transfer energy to slower (colder) moving molecules that they come in contact with.

Through their devices, students were trying to limit the number of molecule collisions between the hot jello liquid molecules and the cold air molecules. Using the “jello baby” gave students a tangible and visible way to observe the effects of that energy transfer.

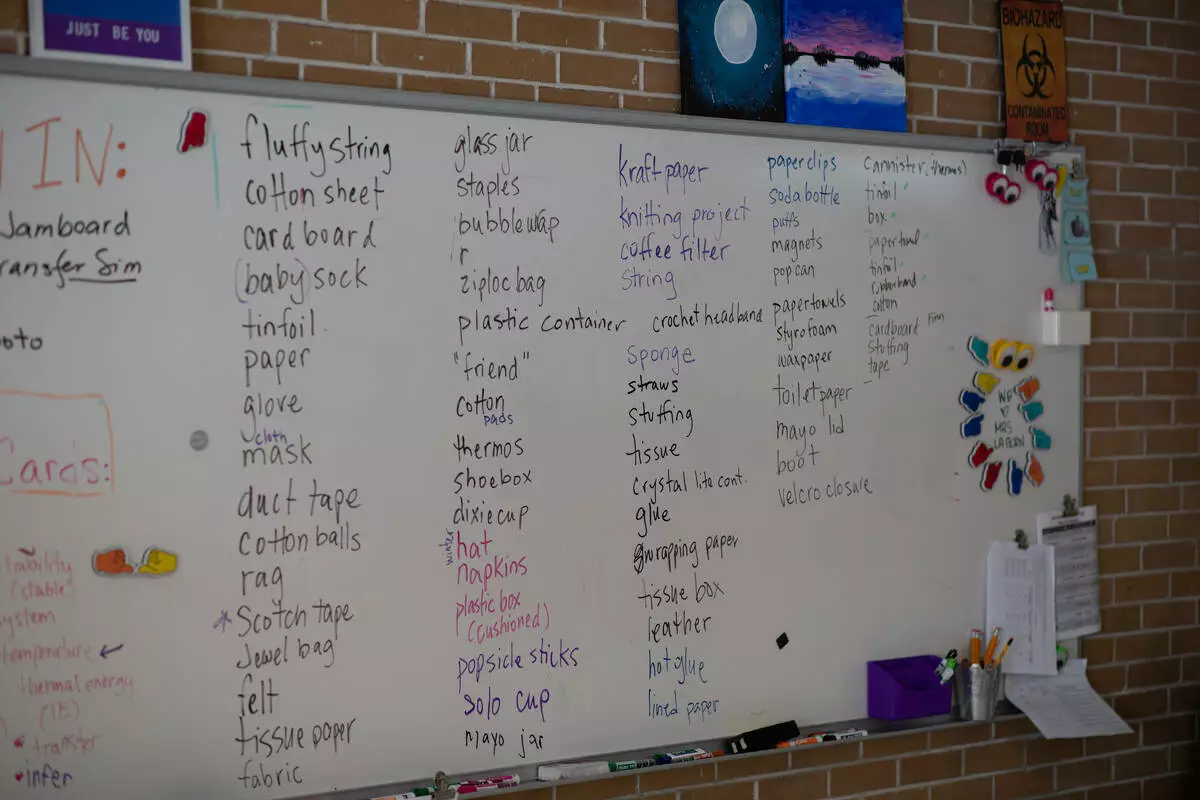

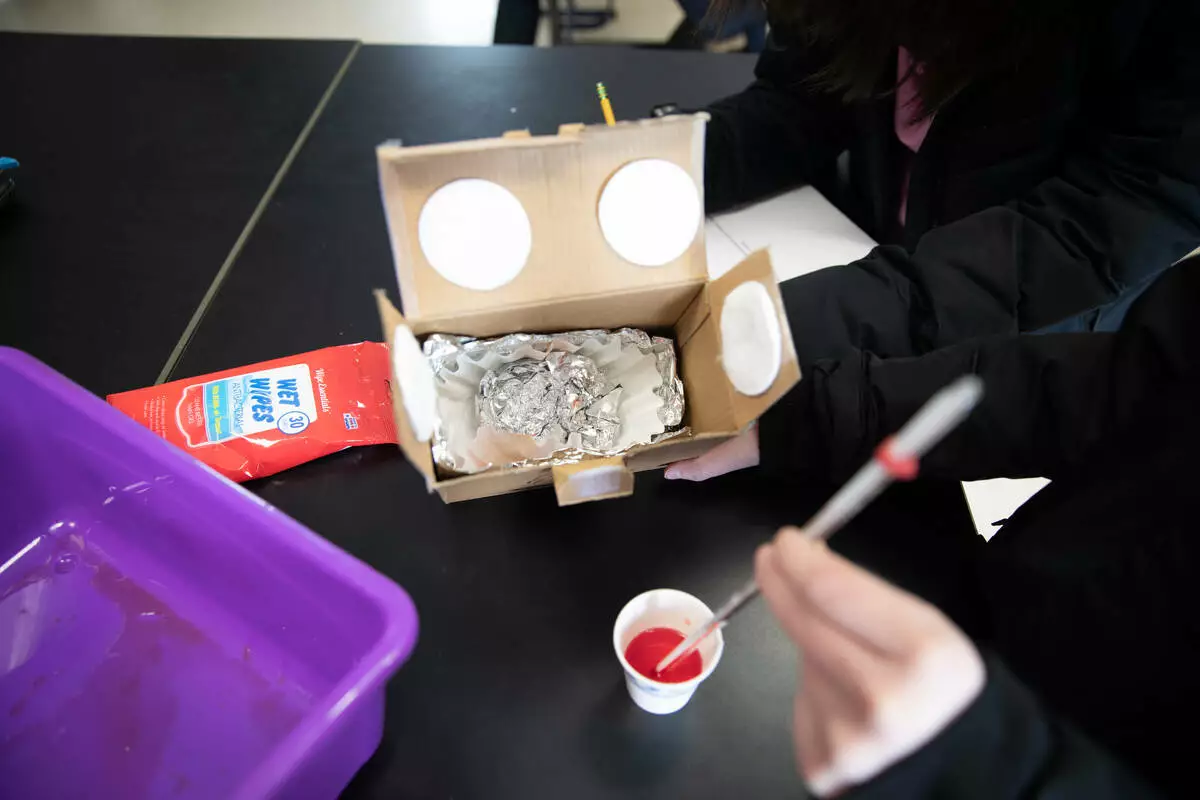

In the days leading up to the outdoor testing, students constructed their devices, choosing from various materials, including paper, cardboard, aluminum foil, duct tape, plastic shopping bags, cotton balls, and much more.

Each of the devices was unique in shape and materials, expressing the kids’ resourcefulness. As groups completed their devices, LaBorn recorded the materials they used on a whiteboard in the classroom to showcase the students’ creativity and facilitate a conversation that would happen the following week about the effects of different types of materials on the loss of thermal energy.

Once constructed, the outdoor component of the lesson would be where students tested their thermal energy retention devices. “Our objective is to try to keep the jello a liquid,” said LaBorn. “If we left it at room temperature, it would eventually solidify. We’re going to drop the temperature significantly for a short amount of time, but students are trying to limit the amount of heat lost, or maintain the thermal energy present in the jello baby, keeping the jello a liquid as long as possible.”

On the day of outdoor testing, students in each of her six classes prepared their devices. First, LaBorn used a hot plate to heat the jello, and using small paper cups, poured a few ounces of the red liquid jello into many small paper cups. The jello starting temperature was recorded, around 40 degrees Celsius.

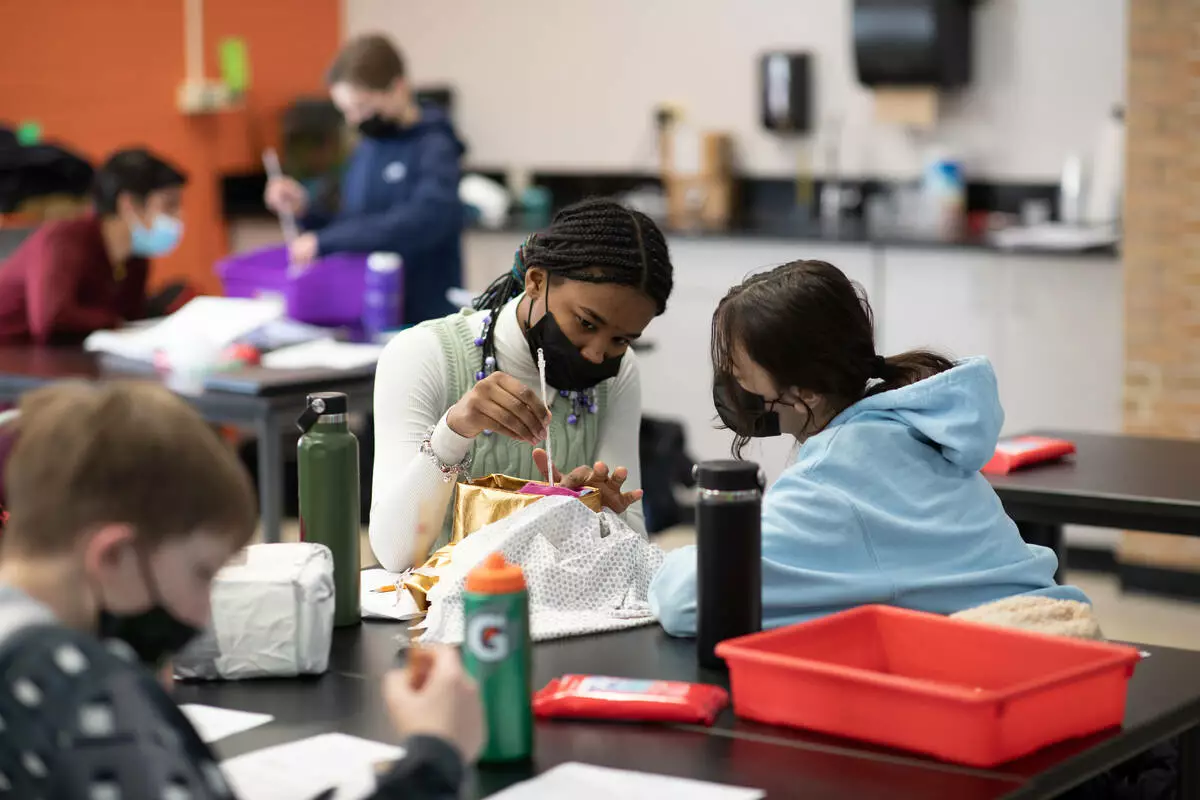

For testing, each pair of students had a job. One student would carry the device outside, while their partner would carry the cup of liquid jello. Together as a class, the students walked outdoors to set them up.

Max Salinas, a 6th grader at Jackson Middle School, was one of the students who built a device with his partner Leo Guerra.

“We used cardboard and a lot of tin foil, and then added paper,” said Salinas. “Then when we got outside, we encased it in snow,” Salinas predicted that the snow would help insulate the liquid jello. His device also included paper clips protruding out to help keep the device stable in the wind.

Ideally, the materials and construction of the device would provide insulation to the liquid jello, specifically when placed in the cold environment.

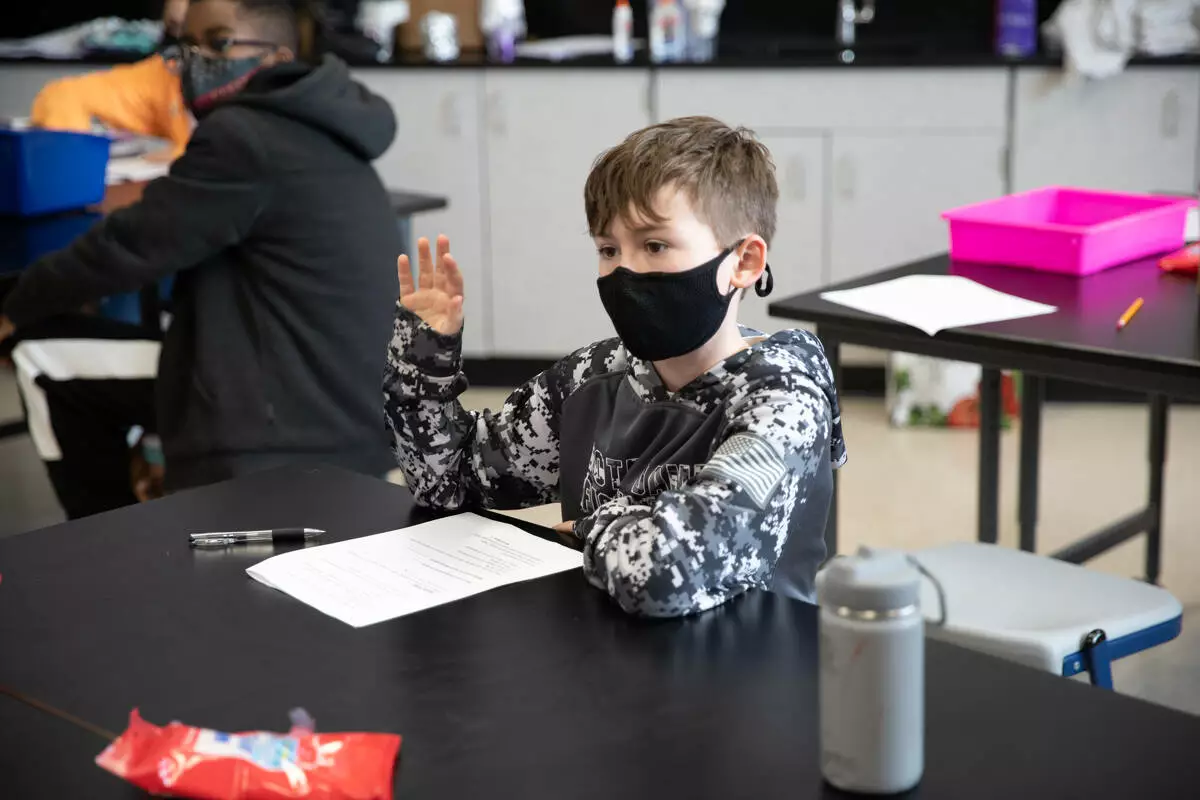

Once the devices were set up outside, the students returned to the classroom and talked about the temperature outside.

LaBorn had a student volunteer hold a thermometer outside a classroom window to get an idea of the current local temperature, and engaged students in a discussion how this might not be the most accurate way to measure temperature, given the transfer of kinetic energy between the different temperatures of the inside and outside air molecules meeting at the window area.

Mrs. LaBorn then visited a weather-based website, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (www.noaa.gov), where she obtained a more accurate reading of the temperature. LaBorn then had students make a prediction about what would happen with their device.

“The predictions could really center on two main things, the temperature of the sample and the shape, or structure,” said LaBorn. “What do you think is going to happen?”

After 20 minutes, the class put their coats back on and returned outside to retrieve their devices and assess what happened.

Back at their desks, students used thermometers to measure the temperature of the jello after it had been in the cold. Some found their jello had remained liquid, while others discovered a semi-solid jello.

Students recorded the starting temperature of the jello, and then recorded the temperature of the jello following 20 minutes of it being outdoors.

Two students, Alyssa Kotcherian and Gabriella Saddler, assessed their device after being outside.

“Our jello was still liquid. I didn’t think it was going to survive because it was all around the snow, but it did,” said Alyssa. “Probably because of the foil.”

Alyssa and Gabriella felt that while the cardboard they used in their device probably didn’t help much, the tin foil they lined it with did help insulate the liquid.

Ella Paulsen and Gabriella Martinez had some unexpected results.

“So we went outside, we saw that our device was spilled over,” said Ella. “We learned that we should have used something heavier,” she said.

Their jello baby had spilled out of the small paper cup. The jello, however, was still inside the clear plastic bag. “It was pure liquid before, but most of it is solid now,” said Gabriella. “The bag was lying sideways on the cement, and that made it become semi-solid.”

Laborn loved the fact that her students were excited about learning science.

“When I announced the experiment and design project, the excitement in the room was palpable,” she said. “As soon as I let them begin discussing and planning, they were up and 100 percent engaged. Every one of my students was focused on coming up with their plan for the design and the materials to bring to class the following day.”

“It was wonderful to see.”